Visions for Transformational Climate Change Adaptation in the Agricultural Sector through Future Design

- Top

- Visions for Transformational Climate Change Adaptation in the Agricultural Sector through Future Design

Visions for Transformational Climate Change Adaptation in the Agricultural Sector through Future Design

A Case Study to Create a Vision with Multi-stakeholders

1. Backgrounds

KCCAC has conducted surveys especially focusing on the heat on the health, as well as agriculture, seeking transformative adaptation based on comprehensive, long-term perspective.

One key finding is that both the climate change impacts and the countermeasures are interrelated and intricately intertwined with other societal and environmental changes. For example, when considering the future of agriculture in Kyoto under climate change, simply introducing crop varieties resistant to high temperatures would not suffice as a comprehensive adaptation strategy. The necessity to take into consideration multiple factors of the future is apparent, including the situations of agricultural land, supply chains, as well as demographics and economic conditions. Moreover, it is crucial to incorporate to ensure conditions for sustainable local communities and to do so, reflecting the voices of local people is essential. To put it another way, relying solely on the scientific basis or local residents’ needs might not lead to effective long-term adaptation strategies. Simultaneously, bringing together people from various fields and perspectives who had never discussed these issues before and having them collaboratively develop adaptation strategies seemed like a significant challenge

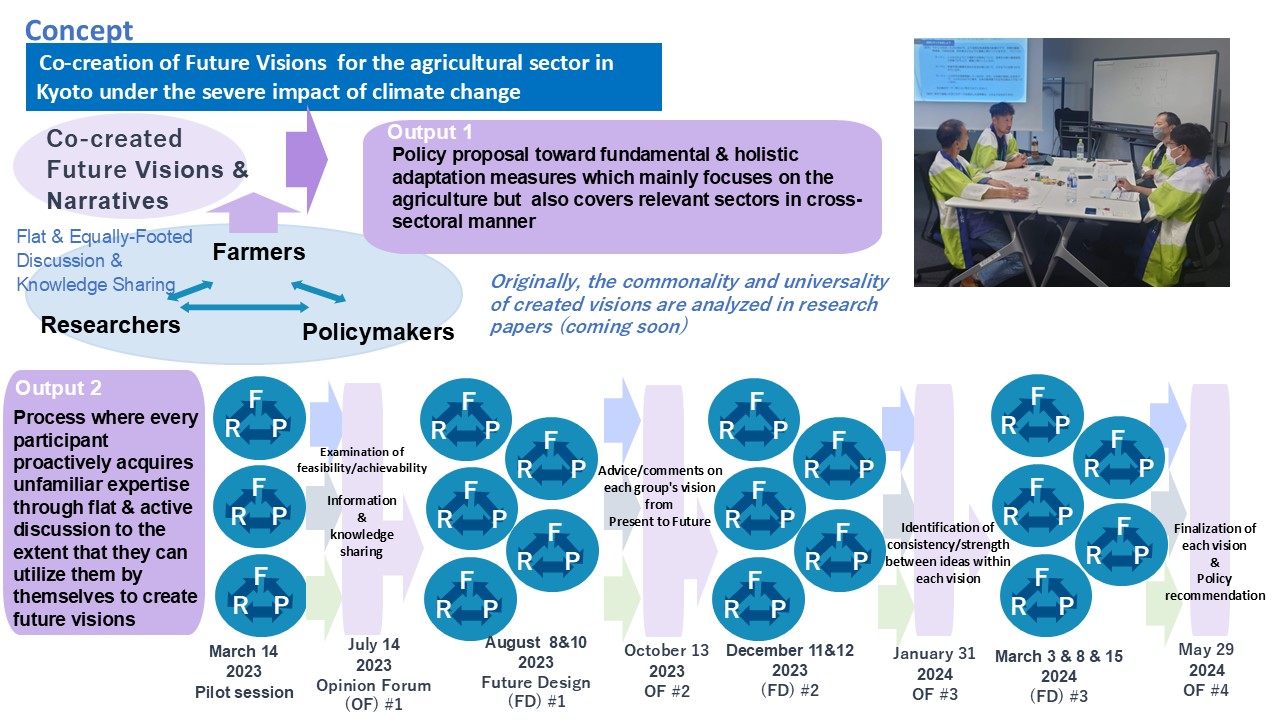

To address the abovementioned issues, we set a key objective: to create a future vision for “agriculture in Kyoto under climate change” through equal-footed flat discussions among together three sectors with different perspectives: farmers, policymakers, and researchers. There, we paid large attention so that each participant could bring unique information and knowledge to the table. Also, we are confident that the generated future vision would be both creative and grounded from a long-term perspective by acknowledging the differing viewpoints of other participants. This is why we adopted the Future Design (FD), a framework that encourages creative thinking and long-term planning. From March 2023 to May 2024, we held a series of sessions, including one pilot session, 4 opinion forums, and FD workshops, where farmers, policymakers and researchers collaborated.

2. A Future That Can Be Created Collaboratory through Future Design (FD)

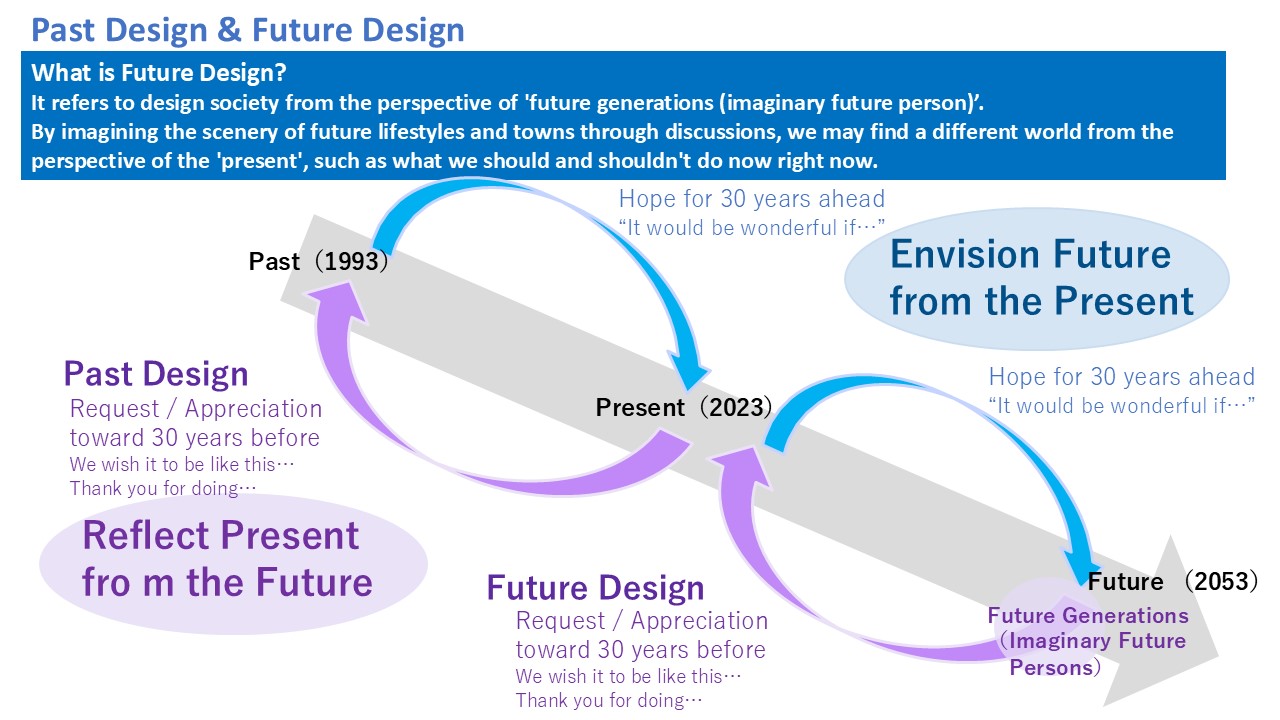

Usually, we envision the future from the present perspective, looking forward to what lies ahead. In FD, the direction is the opposite: we place ourselves several decades into the future, adopting the perspective of an “Imaginary Future Person” (IFP), engaging with the future as if we are living there. From this perspective, the vision of society that emerges is different from what we see when looking forward from the present.

In the actual workshops, a process called “Past Design” is taken. Participants reflect on themselves and the social context of 30 years ago, sending messages —ranging from gratitude to complaints or indifference—to the past generations. By shifting this reflective exercise forward in time, participants find it easier to transition their thinking into the mindset of a future person.

3. A Future Vision That Inspires a Sense of Possibility and Confidence in “We Can Create Our Future”

Today, the Agricultural sector faces multiple challenges, such as aging and a shortage of successors. Additionally, recent increases in heavy rains and high temperatures have led to significant decreases in yields and deteriorations in quality, both of which directly result in a reduction in income. To address such problems, technological advancements are progressing as one solution; they offer possibilities of AI or drone technologies in future agriculture, as well as options like facility-reliant farms for vegetable production.

One group initially envisioned a future where most farmers were mainly facility-reliant to avoid adverse climate change impacts. There, few farmers continued their conventional way of agriculture on land. In this vision, AI manages the growth conditions of vegetables, allowing people without agricultural knowledge to enter the field. They thus address both the risks of extreme weather and the shortage of successors. However, when a participant from academia in the same group asked the participating farmer, “Would you enjoy such a style?” The farmer thought for a second and expressed, “If that’s the case, I wouldn’t want to be a farmer.” This led them to realize that the joy of farming, for some farmers, may lie in interacting with the sun and soil, observing the condition of the crops, and fully utilizing their own skills. With this understanding, the discussion shifted to seek a way to keep conventional farming in the face of intense climate change.

The key point here is that participants from different sectors shared a vision of the year 2053 through the FD process, putting themselves in the shoes of future people living there, and began to outline a concrete path toward that vision together.

The created vision from these discussions involved turning the severe impacts of climate change into opportunities. It focused on a fundamental social transformation where individuals prioritize well-being and the intrinsic satisfaction of their work. Faced with significant uncertainty, people sought out new approaches that did not simply follow conventional paths, embracing a mindset of “let’s try it first.” From the future visions created by five different groups, we have gathered insights into potential adaptation strategies for agricultural sector in Kyoto in the context of climate change.